Today, people living in what we now call Canada are faced with Covid-19, but it is far from being the first epidemic to attack those living on this continent. For the first few centuries after the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, up to 95% of the Indigenous populations lost their lives, in a large part due to new contagious diseases. Those living in “New France” were not spared these horrors.

Today, people living in what we now call Canada are faced with Covid-19, but it is far from being the first epidemic to attack those living on this continent. For the first few centuries after the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, up to 95% of the Indigenous populations lost their lives, in a large part due to new contagious diseases. Those living in “New France” were not spared these horrors.

Particularly active in the region, Jesuit missionaries documented the ravages of these epidemics, alongside their own reactions and those of the Indigenous populations, such as the Huron-Wendat. This history can teach us that back then, as well as today, it was the most vulnerable people in society who suffered the most from epidemics. Even now, many First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities are particularly vulnerable in the face of Covid-19, largely due to a lack of resources such as– much too commonly– running water. Moreover, as with the current pandemic, in the historic epidemics it was the elderly who were especially vulnerable. Responsible for passing down knowledge, their deaths brought about an irreparable cultural loss in their communities. Indeed, this history reminds us that self-isolating saves lives!

How do we know what happened?

The Jesuits wrote frequently about illnesses and epidemics in their Relations, annual reports on their missions. These collections of books and other manuscript documents are, like all historical sources, subjective. The Indigenous perspective on these epidemics, however, lives less in the writings of the Jesuit and more in their own forms of communication, such as oral histories. One of these, (retold by the Ethnologist Marius Barbeau) for instance, tells of a man who received a bottle from a white man containing smallpox, which began to spread before being fought off by the skunk.

Reading these historical records can be shocking. For example, the Jesuits often criticized Indigenous customs, particularly those which contradicted Christian teachings. Missionaries and Europeans in general participated in colonial endeavours which still have negative repercussions today, and readers must be aware of that.

Placed in their historical context, however, how should we understand the goals of the Jesuits? They wanted to save people and even risked their own lives to do so. Even today, as we can read in these same pages, Jesuit works are putting themselves on the front lines in the face of this pandemic, offering their services to those who are suffering.

Epidemics among the Wendat

Whether through direct or indirect contact with Europeans, the Wendat were struck violently by several different epidemics over the course of the 1630s and 1640s which killed almost a third of their communities. In 1634, Fr. Jean de Brébeuf described a sickness with a burning fever, a rash and painful diarrhea. In 1636, a terrible epidemic resembling influenza caused cramps and fevers. In 1639, again, the Wendat were decimated by smallpox. Of course, many Europeans also fell ill to these same diseases, but the results were devastating among Wendat communities.

Why did so many die? Because the Wendat lacked immunity to these new illnesses? This is true to a certain extent, but other aggravating factors closely linked to colonisation (stress, war, malnutrition) also played a significant role. As with today, the virus could strike almost anyone, but not everyone was equally prepared to face it.

Jesuits, the Wendat, and Illness

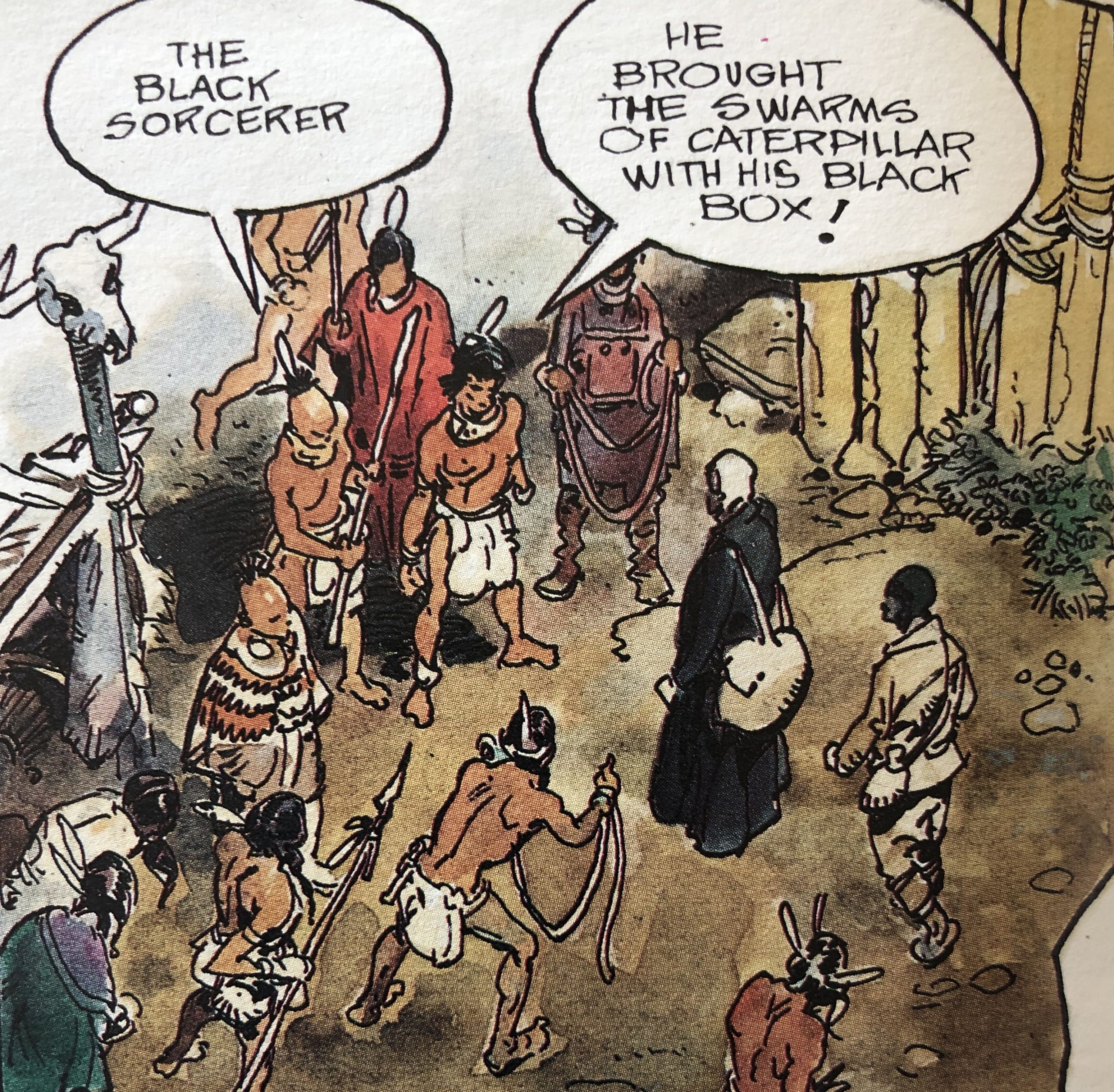

The Wendat and the Jesuits had very different interpretations on illness. For the former, epidemics were believed to be caused by malevolent forces and could be ended by finding the source of evil, or through rituals and remedies.

For the Jesuits, illness was a scourge inflicted by God that could be healed by the “supernatural” side of Catholicism. Missionaries, for example, distributed crosses in an attempt to both heal the sick and show the superiority of the Catholic faith.

During the epidemics, the missionaries visited the sick in their beds not only to try and heal them, but also, above all, to baptise them before their death and save their souls from Hell. These methods, however, had two very different effects.

On the one hand, seeing that the sick treated by the Jesuits often died shortly after, the Wendat accused the missionaries of being sorcerers who caused the deaths and threatened to kill them for their magic.

On the other, many Wendat became more open to the physical and spiritual care offered by the Jesuits. Many among them considered baptism to be a healing ceremony, which the missionaries would complain about elsewhere. The Wendat also added several Jesuit remedies to their own practices, such as sugar or the infamous bloodletting. According to the writings of missionaries, sharing their medicine brought a certain sympathy from the Wendat, as well as the care and attention they charitably gave to the sick.

The Wendat were not the only ones to fall ill during the epidemics, nor to accept “exotic” remedies. For example, in 1637 the missionaries caught the flu and to heal themselves accepted the remedies (but not the ritual sweat lodge) proposed by the shaman Tonneraouanont. Three days later, they were healed, as the shaman had predicted, but they never gave him credit.

Learning more about the history of epidemics can help make sense of what we are currently living through. Want to find out more? We suggest reading, among others, The Heritage of the Circle (George Sioui), A Not So New World (Christopher Parsons) or La Nouvelle-France et le monde (Allan Greer).