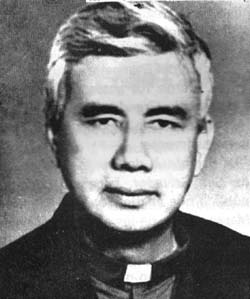

Our chat was supposed to last 15 minutes. I had my questions ready. They were all aimed at trying to discover the man behind the public figure that is Ismael Moreno, a Honduran Jesuit who many simply know as Melo, and who has dedicated his life to defending the freedom of expression and basic rights of the most marginalised and vulnerable people in his country.

Head of the Reflection, Research and Communications Team (ERIC in Spanish) and Radio Progreso, Father Melo has been internationally recognised not only by communities but also by governmental groups, churches, universities and global civil society organisations.

Meanwhile, the fight for justice has entailed serious consequences for him and his colleagues, in the form of countless death threats—to the point where today, he lives under police protection. Some members of his team have paid with their lives.

Meanwhile, the fight for justice has entailed serious consequences for him and his colleagues, in the form of countless death threats—to the point where today, he lives under police protection. Some members of his team have paid with their lives.

“For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places” [Ephesians 6:12].

15 minutes of conversation turned into an hour, and my list of questions was thrown out when I began to listen to Father Melo.

Where does Father Melo find the strength to continue in the face of such dangers? Who is the man behind this fight dedicated to the most marginalised? What’s his story?

In a conversation that turns out to be far less scripted and more relaxed than expected, the answers flow.

Not many people know your story. Can you tell us a bit about your background?

I’m 61 years old. My mother is originally Salvadorean and she came here, to the north coast of Honduras, when she was 6. She walked here with her mother and siblings from El Salvador, a distance of some 800km. I’m the second youngest of 10 children my mother gave birth to, with 5 of us still alive.

I grew up in a humble farm-working family. While my father stayed working the fields, my mother moved to the city, where I started school. I completed secondary school at the Jesuit school in San José. At that time, around the 60s and 70s, here in the city of El Progreso there were 2 schools: one for the poor, and the so-called school for the rich. You can imagine which school was for the rich and which was for the poor. My older brothers had studied at the poor school. And when I finished primary, I should have entered the same one. But that year, the city mayor held a competition to award grants to the 2 most outstanding students. Of 11 schools in the region, I got one of the best overall grades. And so I went to study with the Jesuits.

What made you begin to consider becoming a Jesuit yourself?

Starting to work with the Jesuits in 1972 was a definitive turning point in my life. At the time, there was a group of teachers, some from Spain and others from the USA. I became very good friends with them. They would take me to camps, for walks and other activities. I started giving literacy classes and that was when I got the ‘bug’ for this vocation. I said to myself “So, look, if these guys are so enthusiastic, why can’t I be like them?”

Other experiences have also defined me, such as the murder of my father in 1974. He was a grass-roots peasant-farmer leader, a humble and poor man, but with a very open mentality. He was politically and socially restless.

I was also moved by the presence of Father Guadalupe Carmen, who supported a peasant-farmer organisation. He would be dressed all in white and he accompanied my father as he led a meeting for a grass-roots peasant-farmer co-operative. That experience of personally knowing a priest who worked with the peasants, together with the murder of my father, left a mark on me and led me to think about joining the Society of Jesus.

When did you finally join the Society of Jesus?

The final trigger was the martyrdom of the Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande on 12 March 1977. He was a law student at the National University of Nicaragua, involved in the students’ fight for social justice. On the 12 March 1977, I received news of Father Rutilio’s assassination, and of the threat to the Jesuits from the death squads. They told them that “if you don’t leave within 60 days, you will be killed.” I was shocked that the Jesuits in bloc replied, “We’re staying put in El Salvador.” So I called up a Jesuit—the one who used to accompany me (Father José María Tojeira)—and I told him, “since Father Rutilio Grande has been killed, I will replace him”.

The final trigger was the martyrdom of the Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande on 12 March 1977. He was a law student at the National University of Nicaragua, involved in the students’ fight for social justice. On the 12 March 1977, I received news of Father Rutilio’s assassination, and of the threat to the Jesuits from the death squads. They told them that “if you don’t leave within 60 days, you will be killed.” I was shocked that the Jesuits in bloc replied, “We’re staying put in El Salvador.” So I called up a Jesuit—the one who used to accompany me (Father José María Tojeira)—and I told him, “since Father Rutilio Grande has been killed, I will replace him”.

Have you ever doubted your calling since then?

Over these 40 years in the Society of Jesus, I’ve had many doubts. Normally, they’re related to either the ecclesiastical commitment to the Society of Jesus, or to social movements. But I’ve never had a single doubt about fulfilling my vow to serve the society of the poor. That has never been in doubt for me. Thus, my whole life within the Society of Jesus has been unchanging. I am eternally grateful because, and I mean this in a humble way, they have always allowed me to do what I want—always discussing this, of course, with the superiors and the religious community.

For example, I completed the regency (one of the stages in Jesuit education) in rural communities, first in Nicaragua and then in the north of Honduras. I have served indigenous resistance communities in Guatemala. I have also served sectors during the war in El Salvador and Nicaragua. I thank the Society of Jesus for allowing me to do all of this.

What do you think about violence as a means to achieve justice and peace?

I have lived through the 3 Central American wars: the war in Nicaragua, in El Salvador, and in Guatemala. That was a true experience for me. Therefore, having personally experienced these, I can firmly state that our apostolic mission must always be a contribution to peace, and moreover, our apostolic mission in the service of peace must always be by peaceful means. Profound change must be advanced through peaceful means, because war is never the answer. I say this from personal experience: war and violence can never be the answer in a world that needs to live in peace and where under conditions of justice and dignity must prevail.

On the 16 November 1989, 6 Jesuit priests and 2 laywomen were assassinated on the UCA campus, ordered to lie face down as they were executed.

Can you tell us about your experience working with the Jesuits? In particular with the martyrs of El Salvador?

I did my novitiate in Panama. I then studied Philosophy in Mexico. My theology studies were completed in El Salvador. There, I had the opportunity to take classes with the murdered Jesuits. That profoundly affected my life. I presented my Master’s thesis in Theology in El Salvador in September 1989. That was the last time I saw Ignacio Ellacuría and had dinner with Elva and Celina Ramos, who we were very close to.

I returned to my work in Honduras and when I heard the news about the assassinations of the Jesuits and Elva and Celina, I went with my Jesuit companion to Tocoa, Colón. And I didn’t pass by to say hello to my mother, Alita. So she, who knew all of the murdered priests, called me and said “Son, why didn’t you come by to say hello? Did you not want me to see you cry?” And I replied, “Yes mother, you’re right”. She answered, “Well look, prepare yourself, because if they have killed your colleagues, you mustn’t be afraid. You should prepare yourself in case you also have to give your life for your calling”. That was seared into my heart, because, through my mother’s voice, I feel that I was receiving God’s approval to continue to fulfil his will amid the great difficulties, worries and doubts that I have always encountered on my path.

You’re speaking of doubts related to the Church. Where do you get the motivation to stay in a church that, today, is questioned by many?

It helps me to be humble to myself, but also to my Jesuit brothers. We are part of a church, of an institution, which is often more sinner than saint. But we ourselves are also sinners. What right do I have to so directly disavow a church with vertical institutionality that is so often incapable of listening to the cry of the poor, to adhere to such active norms and sexual morality, if we ourselves often fail to lead an austere life, dignified and devoted to others? That’s for starters.

I dream, for example, of the Vatican state being abolished, because it essentially contradicts the Gospel of Jesus Christ our Lord. I dream, for example, of equal participation in the church between men and women, but that isn’t the reality.

What motivates me to live here and live this life—in joy, even? Look, firstly, I have a very deep faith in God, who makes his presence felt in my life. This is not a distant God, nor a God who punishes, a God who condemns or persecutes, but rather a God so great that one feels he is commensurate to the scale of our fundamental human and spiritual needs. That’s my first sustenance: faith and hope.

My second sustenance is that at 61 years old, I have seen and known dozens of men and women who were killed for their commitment. I could reel off an endless list of names. For me, they are martyrs. That memory is so essential to living my vows, to nourishing my hope and, moreover, to not falter or turn back. If they have given their lives, how can I now live mine without feeling that pinprick that pushes me to give continuity to their commitment amid my weaknesses?

My third source to live joyfully is the closeness and generosity of the communities [I work with]. I live in probably one of the most impoverished countries on the continent. But every weekend when I visit these communities, I am given so much. You’ll find them giving you bananas, oranges, pineapples, melons, beans, tortillas, avocados. They fill you with generosity. They own their poverty to such an extent they share it. They share it and the poverty is then transformed into a shared lunch, a shared embrace, a shared smile and a shared faith. That’s when my faith is strengthened—by the faith of these communities, who in their poverty, share.

The fourth motivation is the formidable team I work with. I work alongside another wonderful Jesuit, the Guatemalan Father Martin Garcia. The rest is made up of 59 laypeople, men and women who receive a small salary. They will never make their fortunes working here on the radio. They put themselves at risk and are threatened with death. However, you will always encounter celebration, joy, generosity and dedication. This team is a gift from God and through them, I too discover where I belong and my strength to keep believing.

The social context in Canada is much more secular. What would you say to a young Canadian who is searching for purpose, looking for meaning?

The same I would say to a young man from Venezuela, Honduras, El Salvador or Spain: “Look, you have the chance to discover profound joys by breaking out of the mould of the lifestyle that has been imposed on us. You will not discover these by yourself, but rather, by walking in community with others.

You will never find them in consumerism, because such joys are always fleeting and will leave you emptier than before. Discover such joys by building a shared life, living in a more simple way. You do not need to accumulate things, chase the latest smartphone, live off appearances; rather, live more simply, with few things, and share these with others.

Ultimately, if you want to discover the deepest joys, try to look at yourself and in those depths, you will emerge full of life to share with others, because others are the ones who bring full meaning to my life. You won’t find the meaning of life only within yourself, but have to look for yourself first to then discover yourself in others, who will bring full meaning to your existence.”

That’s what I would say to a young man, to someone who is searching. Another thing that’s fundamental: the deepest joys are never to be found on the market, in supply and demand. That’s my experience. I find the deepest joys in that which is neither bought nor sold: in gratitude. Friendship, commitment, the struggle for a fairer society, these are things that cannot be bought, they have no price. Surrendering yourself is how you, in turn, fully immerse yourself in a life that isn’t to be found anywhere else on the market.

As part of its editorial policy, Radio Progreso, the station you work for, defends values such as respect for diversity, communities and the inclusion of ideas. Do you personally share those values?

My team and I are convinced that if the church doesn’t change, it’s only going to become increasingly more isolated. Indeed, we need an ecclesiastical overhaul. Why? Because the church we have now hails from a time that no longer exists. And there is resistance to change. By seeking to stay in that time, the church is moving away from our reality and ultimately losing credibility, while also losing the capacity to provide a service to all of society. Thus, the church’s salvation—and to make the Gospels credible—lies in opening itself to a changing world. I don’t mean to say they have to accept everything we’re seeing now in society, but they do have to enter the dialogue. The Church has to open up and converse, debate about different things, because we live in an ever more pluralistic world, an increasingly diverse world. Religion is increasingly becoming just one sphere of this world, and not an entirety. Only by entering the debate can openness be achieved, listening to diverse ideas (the ‘other’) is how we will be able to modernise our mission of evangelisation. The biggest mistake the church is making is shutting itself off, sticking to concepts that completely come up against everyone else’s thinking.

Thus, the church has to enter the debate and listen to the many minority groups, such as for example those representing sexual diversity, women, Indigenous Peoples, and youth in its diverse forms. Because when you listen, you are then open to receiving the good news that is within these various groups, and not just attack them or say “this is bad”. No, I believe that to be a grave error. Only by listening, opening oneself to others, heeding the call, the cry of these various groups, is how the church can prepare itself to give answers in a creative and novel evangelising mission.

Do you have time for leisure? What are your hobbies?

Well, I enjoy doing two things. The first is reading literature, a range of novels. That relaxes me and I can take a break. And also writing stories. I’m not saying they’re any good, not at all (laughs). For example, it might just be that based on this chat we’re having, I’m inspired to write a story about you, what life is like in Canada and so on. I find it fun, a relaxing break. I also relax by going for walks with people from my team. Now I’m getting on in years, but they like sports and at least I go and watch them having fun. I also really enjoy dancing, in trusted environments. I have rheumatoid arthritis, but that doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm or ability to occasionally practice dancing with my friends. Also, I get up at 4.30 a.m. because afterwards, around 5.30, I have a programme on the day’s Gospel, and in the evening I have a cultural programme. So between 4.10 a.m. and 5.30 a.m. I devote a moment to silence, to prayer, begging our Lord for light in order to be, insofar as possible and in view of the limitations, more generous. At the end of the day, after reading a little and writing a bit of the story, I reflect a little on my day in order to see where I went wrong, my limitations and what you and I call ‘soul searching’, to be able to relax, reliving the many minds and voices I’ve encountered during the day.

My days are packed full of activities, but at 5 p.m., I stop everything. Why? Because that’s when I go to visit my mother, who lives 10 minutes from here, from my office. She’s lost many of her abilities, but she has no problem recognising me; we chat, I tell her things, she asks me questions, she always asks me the same thing.

That’s my day, together with rest. In the evening, I have a music programme, Latin American music, called América Libre. I’ve been doing it for 10 years and truth be told, I really enjoy it.

“Living unreservedly in life’s duties, problems, successes and failures, experiences and perplexities. In so doing we throw ourselves completely into the arms of God, taking seriously, not our own sufferings, but those of God in the world—watching with Christ in Gethsemane. That, I think is faith, that is metanoia; and that is how one becomes a [person] and a Christian.”

– Dietrich Bonhoeffer