By Michael Wegenka, SJ

In the summer of my first year of regency at Regis Jesuit High School in Denver, I boarded a plane at Dulles Airport outside of Washington, D.C., and caught connecting flights in London and Baku, Azerbaijan, before arriving at my destination: Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. I had only the first name of a young woman who would greet me in the arrivals lounge once I passed through customs. Thus, I found myself sitting in a chair in an airport that was covered in letters of the Cyrillic alphabet in a former Soviet republic in Central Asia at 3:00 in the morning, waiting for someone named Nasikat to take me to a Jesuit community where I could get some rest.

What had brought me on this journey was a name I first heard many years before: Fr. Anthony (Tony) Corcoran, SJ. He was already something of a legend when I was a novice, and I had never forgotten the conversation we’d had while I was on a novitiate experiment in New Orleans. A few years later, after I took vows, he gave me advice about gratitude in a Subway restaurant in Mississippi. Even then I could see he was a true missionary who lived out his Jesuit vocation with authenticity, and I frequently sought him out as a mentor and friend during those first years of Jesuit formation.

Tony was first missioned to the Russian Region of the Society of Jesus in 1997 and became the regional superior in 2007. In 2012, while in my first year of regency, I contacted him about the possibility of going to Russia for language study. He proposed Kyrgyzstan instead. Looking it up on a map for the first time, I found a country located west of China, south of Kazakhstan, east of Uzbekistan, and north of Tajikistan. It was 12 time zones away from Denver, so I could not have travelled farther away from home without starting to come back.

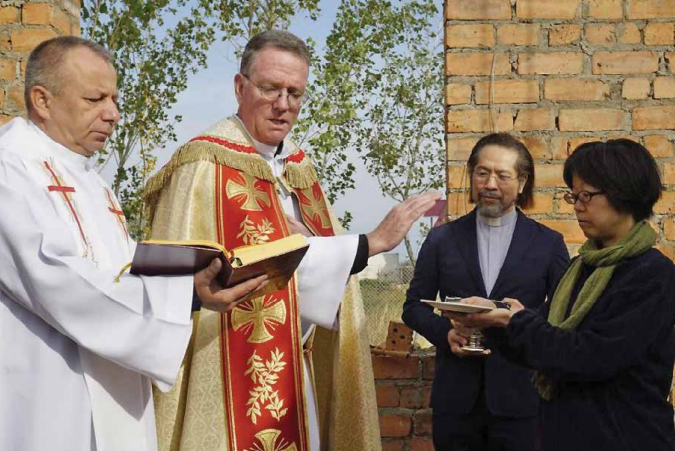

Issyk-Kul Lake in Kyrgyzstan, joins Fr. Anthony Corcoran, SJ, in blessing the

construction of a new building for the center.

In 2017, Pope Francis named Tony the apostolic administrator of Kyrgyzstan, a small Catholic community spread out across a vast area made up of mostly mountains. In this assignment, Tony is now the ordinary (or head) of the church in Kyrgyzstan, which the Holy Father has entrusted to the care of the Society of Jesus. He functions in much the same capacity as a bishop and finds the unusual governing structure of apostolic administrator to be well-suited to a predominantly Muslim country with so few Christians.

“The Church generally creates the structure of Apostolic Administration when the resources of the Church are insufficient to justify construction of a diocesan structure,” Tony explained. “I am convinced that my becoming a bishop within the context of our tiny Christian communities and other aspects of the local society would not necessarily help me to better serve our people. Of course, the authority to make such a decision belongs solely to the Holy Father.”

There is perhaps something particularly Jesuit about the fact that Tony reports directly to Pope Francis and collaborates so closely with other Jesuits to provide the sacraments and material aid to the people of Kyrgyzstan. But his obedience to the Holy Father has led him far from home.

The Grace of Being Small

Kyrgyzstan’s economy is based largely on agriculture and nearly one third of its population lives below the poverty level. In a population of nearly 6.5 million, fewer than 2,000 are Catholic.

When I first spoke to Tony on the phone in 2012, he told me that Kyrgyzstan is small. He described it as a “little flower” that was both easy to fall in love with and so delicate as to need especially attentive care. He recently described the Holy Father’s affection for these kinds of places.

“When we met with Pope Francis during the ad limina visit in 2019, he encouraged us leaders of the local Churches in Central Asia to understand that the Church here was really a germoglio,” Tony said. “During our common reflection, we drew out the significance of what it means to be this ‘bud’ or ‘sprig.’ The Holy Father also spoke about how God especially loves to work through the very small.”

I understood this as a willingness to labor without any guarantee of immediate and lasting fruits or benefits. Instead, the work in such small places begins discreetly and waits patiently for growth in God’s time.

For Tony, this faithful patience is something that he first recognized in the people he ministered to in Russia.

“When I first arrived in the former Soviet Union to serve, I was frequently struck by the level of fidelity of many Christians to their faith in Christ and His Church in spite of unimaginable challenges and persistent persecution,” he said. “I met people who had longed to receive the sacraments for decades, even when there seemed little likelihood that this would ever be possible. If those first years of ministry in Siberia and in other places in the former Soviet Union introduced me to remarkable Christian witness, my current assignment demands a newer mode of evangelization within an extraordinarily complex situation.”

When Nasikat greeted me in the arrivals lounge of the airport in Bishkek, I realized that living in Kyrgyzstan would require me to become small, too. This was first reflected in the necessity of bending my six-foot-three frame under the showerhead in my new home in Bishkek, that was only a few feet off the ground. I couldn’t help but laugh at how humbling this was for a foreigner who had just arrived in a much “smaller” world.

I learned to conduct myself humbly by asking for even the most basic things, typically through the universal language of pointing and making facial expressions to convey what my words could not.

A primary reason for my journey to Kyrgyzstan was to learn Russian, and my inability to speak the language ultimately meant that much of my time there was spent in silence. At one point, it struck me as being similar to being on a silent retreat. I became increasingly more attuned to what was going on within and around me as time progressed.

I did most of my speaking during the English lessons I taught to young men and women at a summer camp near what can only be described as a great lake in the eastern part of the country, Lake Issyk-Kul. My students were intensely interested in anything I could tell them about American culture. These conversations in English opened to them a larger world that they had only seen images of on television screens or their phones. It soon became clear that this big, American world was clamoring mightily for their attention – all the way across 12 time zones and thousands of miles of land and sea.

Pandemic Impact

Kyrgyzstan locked down for two months last spring because of the coronavirus pandemic. Since then, the country has experienced a political uprising and passed through wave after wave of illness and economic hardship. However, the pandemic has also invited new engagements between Christians and Muslims that would not have been possible before. The tremendous needs of the poor demand collaboration among groups that would have otherwise been unlikely to work together.

However, the pandemic did little to arrest the perennial issue of the emigration of many Kyrgyz people to Russia and Europe. Even my own ministry of teaching English likely helped prepare some of my students to one day emigrate to another country where they may be better able to lift themselves out of the poverty that is so common in Kyrgyzstan.

Despite the challenges and hardships that so many of his people face, Tony is quick to point to the even greater graces he sees each day.

“The sincerity of faith in many of our people remains striking,” he said, citing a recent visit to villages to celebrate the sacraments of confirmation and baptism after an absence of more than a year. “I found myself once again moved, somehow even surprised, in witnessing the evident consolation on the faces of family members as they prayed the Creed and during and following the reception of these Sacraments. I subsequently have often meditated on these faces … and on the surprising fact that God still causes this sense of ‘wonder’ in His pastors.”

The faces of the Kyrgyz church continue to give lasting encouragement to the Jesuits who have travelled so far to be with them.

Coming Home

Toward the end of my time in Kyrgyzstan, I had an opportunity to travel up a mountain valley with a group of teenagers. Along the idyllic mountain path that wove in and out among streams and tall grass, we came upon a Kyrgyz farmer who lived in the valley and milked his horse to sell to those who happened along. The horse milk he offered us (known as “kumis”) was fermented, and he and the teenagers I was travelling with laughed heartily at my face when I took the first sip. It is, I suppose, something of an acquired taste. It was a moment, nonetheless, when I most felt like one of them, drinking the same beverage that had nurtured the people of Central Asia for centuries.

Just a few days later, on the feast of St. Ignatius Loyola, I celebrated an early morning Mass with the Jesuit community in Bishkek. I then boarded a plane back to Baku, then to London and finally to Denver. Returning to the United States, I attended a late evening Mass on the same feast day of St. Ignatius with my Jesuit community in Denver. Thanks to those 12 time zones, I enjoyed a 36-hour-long feast day on opposite sides of the world and was left to reflect on how much I was at home in both because of the common bonds I shared with the Jesuits in each.

When I asked Tony recently about where he feels at home these days, he answered it in the most Jesuit way possible. “For most of us, this is not meant to be such a difficult question, since we can endeavor to be ‘at home’ precisely where we have been assigned to serve.”

Nevertheless, it is still the case, he said, “that all of us Jesuits can agree with the conviction that there are certain essential elements of the Jesuit vocation that demand not only continuous recommitment / re-animation, but which in effect define the quality and vibrancy of our Jesuit lives.”

This availability that first brings a Jesuit across the world to serve as a missionary must be renewed each day regardless of where he finds himself working.

“As I was preparing to depart for Siberia as a young Jesuit priest, one of the elderly Jesuit missionaries I met advised me to continuously beg from God the grace to ‘fall absolutely in love’ with the people to whom I was being given and even to love their language and culture. He called this – along with a deep trust in and abiding love of Christ and His Church – the most important grace of a missionary. Almost a quarter of a century later, I remain amazed at the wisdom of this advice – and at the inexplicable generosity of God in hearing this ongoing and sometimes difficult prayer.”

It is clear that Tony has indeed fallen in love with the people of Kyrgyzstan and made his home among them. “The nature of my assignment as apostolic administrator – pastor – of these specific people – entails a commitment to remaining with them. ‘Their fate must become my fate!’ as one of my friends remarked.”

Tony’s future in Kyrgyzstan will be decided by ecclesial leaders and by the playing out of political events in the country. In the meantime, he is attempting to apply for Kyrgyz citizenship and trying to learn the Kyrgyz language, the primary tongue of most people in this country.

“Feeling at ‘home’ here is not such a big problem,” he says, “since apparently God really does love to work through the small – and because He answers prayers.”

May God continue to bless the Kyrgyz people with the grace of fidelity and many more Jesuit missionaries to carry on the work of the Holy Father in Central Asia.

Father Michael Wegenka, SJ, currently serves as director of pastoral ministry and teacher of English at Strake Jesuit College Preparatory School in Houston.